Article Details

As artificial intelligence becomes more prominent, we explore the opportunities, risks and challenges in bid writing.

Background

Artificial intelligence (AI) is nothing new: the term first came into use in the 1950s, with ongoing advancements throughout the decades that followed. The first ‘chatbot’ was created as early as 1966. In 1997, the IBM-developed computer Deep Blue successfully beat the then-world champion Gary Kasparov in a game of chess, and by 2003 NASA was exploring the surface of Mars with its rovers Spirit and Opportunity, each operating without human intervention.

However, the past 10 years have seen AI advance in leaps and bounds. Systems developed since 2020 have represented a step change in the power, reach and capabilities of the technology, with significant media attention on large language models such as GPT-3, developed by OpenAI, and specifically the ChatGPT chatbot that uses it.

Previously, natural language processing models were seen to have limited and niche applications. With ChatGPT – and a string of similar models that followed – the focus shifted, with countless applications and widespread appeal, borne from the technology’s ability to quickly and competently produce high-quality, detailed and accurate written content. The results are undoubtedly impressive: presented with even a simple prompt, ChatGPT (now operating with the GPT-4 model) can produce large amounts of text, which can at times be indistinguishable from that produced by a human author.

A common misconception is that technologies such as ChatGPT ‘search’ for responses to the user’s prompt and ‘synthesise’ results by bringing together pre-existing information. However, in reality the technology is much more sophisticated. Instead, it works predictively, creating content in real time, predicting what ‘token’ or section of text is most likely to come next based on what has come prior to generate its responses. This distinction is important, as it means that the technology can take complex prompts to produce content on a given topic in a particular style and tone of voice, and create something all-new – not just a ‘Frankenstein’ response that cobbles together pieces of information scraped from various sources, but a truly original piece of writing.

Applications of AI for bid writing

Bidding for contracts is a complex process with numerous moving parts. It requires effective project management, strategising, capture planning, document control and communication – but, at its heart, is the fundamental activity of bid writing: writing persuasive responses to quality questions, effectively serving as the bidder’s proposal for delivery of the contract.

The exponential rise in the capabilities and prevalence of AI presents some immediate potential applications for bidder organisations. Can a tender question be simply pasted into ChatGPT or a similar chatbot to produce a response?

Generic responses such as the above – which, in full, went on to identify and outline eight potential approaches to embedding Fair Work First principles – can be generated in a matter of seconds.

Faced with challenges such as tight time constraints, complex quality criteria and the need for detailed responses, bidder organisations may look to the new capabilities of AI models as a panacea: a ‘cure-all’ solution that takes away all their problems. The days and weeks that are ordinarily spent writing tender responses are boiled down into a matter of hours inputting questions in ChatGPT, which simply ‘punches out’ all-new responses, complete with impeccable grammar and clarity of language, all organised into easy-to-read lists.

Can it really be that simple?

To answer that question, it’s important to take a step back and remind ourselves of the purpose of the competitive tender process. What are evaluators really looking for in a tender response?

Ultimately, the tender process exists to enable buyers to make effective best-value decisions in procurement. Alongside considering price, buyers need to consider non-price factors, such as the effectiveness of bidders’ proposed service delivery models; approaches to contract management, quality management and the environment; their plans for resourcing and business continuity; and their proposals for creating social value or community benefits local to the area of service delivery. When reviewing a tender response, evaluators are not simply looking for an impressive answer to the question, or for bidders to demonstrate their general competence, knowledge or understanding of the topic. Instead, they want to know about the particular bidder organisation and their particular plans for service delivery: what specifically they propose to do and how they propose to do it, such that the particular aims of the service are achieved and optimal value for money delivered.

Limitations of AI for bid writing

This is where bidder organisations should again take a step back and re-examine the quality of response created through AI. Looking past the veneer of the well-written, grammatically precise and seemingly detailed content, ultimately we find a response that is inherently generic. Trained, competent evaluators working as part of a procurement team know their aim: not to identify a bidder organisation with a well-written, competent and on-topic set of responses, but rather the bidder with the best solution to their requirements. Responses must, by definition, detail what specifically the individual bidder organisation proposes to do, how they propose to do it, the specific benefits of doing it that way, and evidence to demonstrate their capability to do so.

At the end of the day, a tender submission is a proposal. If a tender doesn’t describe what exactly the bidder organisation proposes to do, it fundamentally hasn’t achieved its aims.

AI-generated responses which look impressive but are ultimately generic cannot – and will not – meet evaluators’ expectations.

Risks of using AI in bid writing

It would be naïve to think that some of those limitations cannot be overcome. With GPT-4, it has become possible for bidders to input detailed information from their bid libraries into ChatGPT, effectively ‘training’ the chatbot to develop a baseline understanding of their organisation and their systems, with subsequent responses incorporating the organisation’s tone of voice and key information about their resources, systems and processes. This can go some of the way to making responses feel less generic and more specific to the bidder – but, in doing so, they also expose themselves to significant risks.

Whilst there may be options to opt out of data input into the system being used by developers to train future iterations of their systems, there is never a guarantee that private and confidential information input into a chatbot is protected from breach or misuse, either wilful or accidental. We have already seen ChatGPT banned in countless institutions and even countries, with the Italian data protection authority citing concerns over protection of personal data. Given that tendering successfully requires bidders to disclose their competitive advantages, company strategy and potential trade secrets, inputting reams of highly private and commercial information into such a novel platform carries extremely high risks, with developers such as OpenAI themselves even emphasising that users should not do so.

The confidentiality risks in themselves are severe and significant, but bidders should also consider the equally significant commercial risks. Evaluators who identify responses as being AI-generated – if, for example, responses submitted by numerous bidders are assessed to be suspiciously similar – may deem the submission not to be an accurate and truthful reflection of the bidder organisation and their proposed approach to service delivery. This could in theory result in disqualification from the tender process, reputational damage and possibly even being barred from future competitions.

Even if the risks above were put aside, the fact still remains that a response generated via AI will, by definition, lack the unique insight into the bidder’s specific plans for delivering the particular contract tendered for – which is exactly what the competitive tender procedure was designed to identify in the first place.

Potential impact

Is there a potential for AI to ‘raise the floor’, with competitors who previously failed to hit the mark now able to produce responses which may not necessarily be competitive but are nonetheless competent and compliant – in turn making the need to stand out from the crowd even greater?

Regardless of whether Executive Compass and other commentators would advise the use of AI for bid writing, it is inevitable that many companies will do so, with a direct impact for all other participants in the tender process.

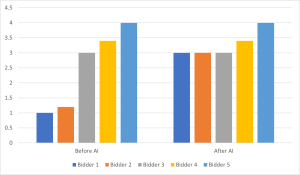

Where previously the field of bidders may have included numerous participants whose responses failed to meet the minimum criteria, the use of AI may enable lower-quality bidders to bring their responses up to a higher standard – generic, but nonetheless competent and acceptable. Similarly, the potential to streamline the tender process may result in more participants in a typical process, putting a further ‘squeeze’ on bidders in the middle of the pack as competition intensifies. Where an acceptable standard of response may have previously led to the occasional outcome, it is likely that more and more bidders will be able to tender to that same acceptable standard, making a focus on excellence, competitiveness and a truly bespoke bid, uniquely responding to the buyer’s outcomes, even more crucial.

Potential impact of increased prevalence of AI in competitive tendering. Before the use of AI, Bidder 3 may have stood out from the crowd of lower-quality competitors (Bidders 1 and 2). With the use of AI, Bidders 1 and 2 may be able to achieve an acceptable standard of generic response, making Bidder 3’s need for excellence in its responses even greater.

Beyond the primary impact for bidders themselves, it is also expected that certain aspects of the tender procedure itself may need to be updated, allowing buyers to cut through the noise of AI use in bidders’ responses and clearly identify the preferred bidder, able to offer best value:

- Early speculation includes the potential increase in scenario-based questions. Whilst models such as GPT-4 can fare well at producing credible responses to hypothetical scenarios, they would still lack the insight that a human subject matter expert could bring to the table, as well as the ever-crucial focus on service-specific details and buyer’s unique requirements.

- Similarly, bidders may see a greater focus on experience-based questioning within tenders: whilst forward-looking responses may enable boundless creativity, focusing on bidders’ past experience may help to ensure that only real-world information be included.

Neither of these approaches would be without its drawbacks, with experience-based questions in particular potentially disadvantaging small to medium-sized enterprises and more newly incorporated organisations, and it does still remain to be seen how exactly buyers might respond.

Executive Compass’s stance

Executive Compass is committed to offering its customers the best possible chance of being successful and excellent value for money, and we owe it to our clients to explore the potential applications of AI for bid writing in serious depth. We have done so, with countless hours of testing, experimentation and assessment. What we have concluded is:

- Due to both the risks and the limitations associated with the technology, it is neither appropriate nor possible at this time for AI to achieve the same standard of response as a human author. Whilst impressive at the surface level, AI-generated responses are inherently generic, not only rendering them weak but also potentially opening the bidder up to accusations of collusion, or even outright rejection. Overcoming this requires the input of confidential and highly commercial information into the platform, exposing the bidder to significant confidentiality risks, and even then the standard of response is not comparable to that of a skilled human author in its specificity, persuasiveness and competitiveness.

- At this time, AI can serve as a powerful tool to support bid writers’ research. Supplementing rather than replacing traditional methods, chatbots can be used to generate further ideas of potential commitments and methods, which a skilful bid professional can weigh up and incorporate into the narrative as they see fit, enabling more comprehensive and detailed responses. Part of the bid writer’s expertise will be identifying how to contextualise and incorporate the ideas to best effect, consistent with the particular bidder organisation, local area of service delivery, buyer and contract – in the exact same way that they would for any additional ideas identified through research within bid libraries or trusted online resources.

Given the exponential progress of artificial intelligence’s capabilities, Executive Compass – just like countless other organisations – will continue to monitor developments closely, with a risk-conscious but forward-thinking mindset. If and when new applications of AI become feasible, we will explore, risk assess and evaluate them, maintaining our focus on supporting bidders to win more work through high-quality tender submissions, and in line with our guiding values of excellence, accountability and ethics.